"The Mechanical Detective," by John Longenbaugh, in Mystery Weekly Magazine, October 2017.

The more observant among you may be wondering why I am reviewing a story in the October issue of Mystery Weekly Magazine when last week I covered a tale from their November issue. The answer is that I am a wild soul, a born free spirit who scorns chronological order. Ha ha!

Sorry. Where was I? Oh, yes.

Another thing I scorn is fan fiction, where a person attempts to add another story to someone else's ouevre, either taking advantage of public domain, or with permission of the heirs, or just hoping that they will never notice or care to sue. Not fond of those stories. But I sometimes enjoy what I call a pastiche in which the writer uses elements of another writers world to create something different. Heck, I have even indulged in that game myself.

And so has Longenbaugh. In his world it is 1889, eight years after the Great Detective (unnamed, but you-know-who) has arrived on the scene, and London is stinky with consulting detectives, each with their own gimmick. Allow me to introduce Ponder Wright, the Mechanical Detective.

Wright is not truly mechanical but rather what we would call a cyborg, having had various parts of his body replaced by machinery after an accident. This was due to the kindness of his wealthy and influential brother. "I daresay my soul is my own," he notes, "but far too much of the rest of me is merely leased from Mordecai."

He says this, by the way, to his roommate and biographer, Danvers, who is a "mechanical surgeon,"

fully human, but skilled at repairing delicate bio-gadgets.

In this story Wright has been summoned to examine the case of a professor who has apparently been killed by one of his automatons. But these robots can only do what they have been programmed to do. Has the War Department violated treaties by asking the professor to build killing machines? Or is there another explanation?

One thing that requires an explanation, of course, is how steam-powered London possesses such advanced machinery. Longenbaugh offers one which requires more suspension of disbelief that Ponder Wright's solution to the mystery, but I enjoyed it all. This is a fun piece of work.

Sunday, November 26, 2017

Monday, November 20, 2017

The Last Evil, by David Vardeman

"The Last Evil," by David Vardeman, in Mystery Weekly Magazine, November 2017.

Hooboy. What to say about this week's entry? It reminded me of Shirley Jackson, John Collier, maybe some shadowy corners of Flannery O'Connor and even James Thurber. In other words, we are in the strange part of town.

Our protagonist is Mrs. Box, who believes that suffering is good for the soul. Hence she wears flannel lined with canvas, because parochial school taught her "the value of chafing."

She also believed in doing "a lot of good in the world. But there was another tinier but just as important point, and that was to get the leap on people. In her own life she felt a lack of people leaping out at her. In the past forty days and forty nights, not one soul, nothing, had given her a good jolt. Mr. Box certainly had not."

Which is why she keeps a live tarantula in her purse, which she pulls out to shock people. As a good deed. Or does she do that?

One thing she does do is meet a man on a train who has something in his briefcase even more frightening than a live tarantula. Or does he?

Enough. Read the thing and find out. It's worth the trip.

Hooboy. What to say about this week's entry? It reminded me of Shirley Jackson, John Collier, maybe some shadowy corners of Flannery O'Connor and even James Thurber. In other words, we are in the strange part of town.

Our protagonist is Mrs. Box, who believes that suffering is good for the soul. Hence she wears flannel lined with canvas, because parochial school taught her "the value of chafing."

She also believed in doing "a lot of good in the world. But there was another tinier but just as important point, and that was to get the leap on people. In her own life she felt a lack of people leaping out at her. In the past forty days and forty nights, not one soul, nothing, had given her a good jolt. Mr. Box certainly had not."

Which is why she keeps a live tarantula in her purse, which she pulls out to shock people. As a good deed. Or does she do that?

One thing she does do is meet a man on a train who has something in his briefcase even more frightening than a live tarantula. Or does he?

Enough. Read the thing and find out. It's worth the trip.

Sunday, November 12, 2017

Precision Thinking, by Jim Fusilli

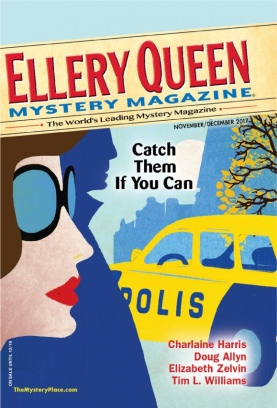

"Precision Thinking," by Jim Fusilli, in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, November/December 2017.

"Precision Thinking," by Jim Fusilli, in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, November/December 2017.Last week I wrote about a story that felt like it belonged in Black Mask Magazine. By coincidence I am now covering a story that appears in the Black Mask department of Ellery Queen. Go figure.

World War II has just started and the German owner of Delmenhorst Flooring has just died. The business is in Narrows Gate, a fictional town which strongly resembles Hoboken, NJ. The Farcolini family decide to take over the flooring business, replacing the German employees with "locals, mostly Sicilians and Italians who couldn't spell linoleum on a bet but had a genius for theft."

It's a cliche, I suppose, that gangsters take a successful business and turn it crooked, even though it was making good money on the up and up, because they can't imagine not doing it crooked. See the fable of the scorpion and the frog.

But in this case there is a low-level mobster who discovers he likes laying linoleum, and he's good at it. Can he find a way to keep the crooks from ruining a good thing?

Fusilli captures the tough guy tone perfectly, in a fun tale.

Sunday, November 5, 2017

"The Black Hand," by Peter W.J. Hayes

"The Black Hand," by Peter W.J. Hayes, in Malice Domestic: Murder Most Historical, edited by Verena Rose, Rita Owen, and Shawn Reilly, Simmons.

It seems like every year or so I have to chide some editors who don't know what a noir story is supposed to be. Today I feel like I have the same problem in reverse. Sort of.

I am not sure of the definition of a "Malice Domestic" story, but I know this one is not what I expected, or what the rest of the anthology (so far) led me to anticipate. Hayes' story is not cozy. It would, on the other hand, would feel quite cozy between the pages of Black Mask, circa 1928, which is around the time it is set.

Brothers Jake and David fought over a girl named Bridgid and Jake left Pittsburgh for logging work in the midwest. David became a very successful mobster, until his body shows up in a river.

The story begins with Jake coming home to try to discover how his brother died and who is responsible. The first thing he learns is that Bridgid was murdered a few weeks before, and a lot of people think David killed her. Is there a connection between the deaths? Can Jake stay alive long enough to find out?

This is an excellent salute to a classic subgenre of pulp fiction.

It seems like every year or so I have to chide some editors who don't know what a noir story is supposed to be. Today I feel like I have the same problem in reverse. Sort of.

I am not sure of the definition of a "Malice Domestic" story, but I know this one is not what I expected, or what the rest of the anthology (so far) led me to anticipate. Hayes' story is not cozy. It would, on the other hand, would feel quite cozy between the pages of Black Mask, circa 1928, which is around the time it is set.

Brothers Jake and David fought over a girl named Bridgid and Jake left Pittsburgh for logging work in the midwest. David became a very successful mobster, until his body shows up in a river.

The story begins with Jake coming home to try to discover how his brother died and who is responsible. The first thing he learns is that Bridgid was murdered a few weeks before, and a lot of people think David killed her. Is there a connection between the deaths? Can Jake stay alive long enough to find out?

This is an excellent salute to a classic subgenre of pulp fiction.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)