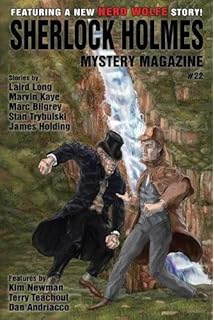

"A Clown at Midnight," by Marc Bilgrey, in Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, #22.

I

have talked before about the characteristics my favorite stories tend

to have in common. One is "heightened language," by which I mean that

the words do something more than just get you from the beginning to the

end of the tale. Usually that means high-falutin' talk, but in this

case, it is the flat, declarative sentences that Bilgrey uses to ground

us in a bizarre tale.

Stevens asked Jack if he knew

what time it was. Jack shrugged and said that he thought it was about

ten thirty. Stevens told him it was eleven and that the store opened at

ten. Stevens frowned and said that had this been an isolated

incident...

Jack dreams of a creepy clown. He

has done it all his life: a recurring nightmare of a clown who chases

him and tries to strangle him. This has ruined his life, destroying his

sleep, which loses him jobs, ruins relationships, etc. Various

treatments have been no help at all.

A friend suggests a

hypnotist who helps him find the root of the problem: an actual assault

when he was seven. With some clever research he figures out who that

clown had been. Now, what to do about it?

It might be time to remember the old saying, supposedly from Confucius, about what you should do before you seek revenge...

Also, a nod to Robert Bloch here. Who wrote the essay suggesting the disturbing nature of the Clown standing out in the street at Midnight.

ReplyDeleteI like what you wrote about "heightened language." It's not what you write, it's how you write it. To me, a strong voice is everything to a story. And you can't fake that. It takes years of practice to build that special vocabulary. Describing something in great detail isn't enough; in fact, it's usually too much. The trick is to write in a unique, evocative, and economical way. Great post!

ReplyDelete