"The Projectionist," by Joe R. Lansdale, in In Sunlight or in Shadow, edited by Lawrence Block, Pegasus Books, 2016.

A warning: this is not a collection of crime stories, per se. The connecting thread is that they are all inspired by paintings of Edward Hopper. No doubt that this story is about crime, though.

The narrator is a projectionist at a movie theatre. He's naive and not that bright - one character calls him a "retard" but that's not fair. The job is okay, and then Sally arrives. Sally is an usherette, and beautiful.

Sounds like we are building up to a classic noir plot, but that's not quite the way it happens. Instead the theatre gets a visit from The Community Protection Board, a bunch of shakedown artists who threaten the theatre and Sally.

But they underestimate our hero. He's seen some bad times and knows some bad people. And soon the Protection Board may need protection...

I must say that of all the stories this one felt most to me like a Hopper painting.

Sunday, January 1, 2017

Sunday, December 25, 2016

The Wait, by Flávio Carneiro

"The Wait," by Flávio Carneiro, in Rio Noir, edited by Tony Bellotto, Akashic Books, 2016.

Bear with me. This may get a little philosophical at the start. We will get to the story.

I would like to suggest that some fiction really is genre fiction and some uses genre fiction. Wears it like a cloak to cover what is really going on. And that isn't necessarily a bad thing.

Jorge Luis Borges' brilliant story "The Garden of Forking Paths" is about a spy doing spy things. But is it a spy story? Not exactly. Is George Orwell's Animal Farm a fable or a political satire that uses the fable form?

Okay. Getting to this week's favorite. A beautiful woman walks into the office of a private eye. Sound familiar?

Detective Andre has an office in downtown Rio. Marina wants him to find a man. Again, still familiar.

But now the ground shifts under us a bit. All she knows about the man is that he has been following her every day for weeks. Now he has stopped and she wants him to start again.

Andre and his sidekick, Fats - or is Fats the brains of the operation? - set out to find the guy. Much philosphizing occurs. Roland Barthes is invoked.

The place where what we might call experimental fiction - those cloaked-in-genre things - tend to fall apart is the ending. Some of these authors seem to take pride in not writing the last page, leaving you wondering what happened and why you bothered to read the damned thing.

Carniero is not guilty of that. I found his ending quite satisfactory, as was the whole story.

Bear with me. This may get a little philosophical at the start. We will get to the story.

I would like to suggest that some fiction really is genre fiction and some uses genre fiction. Wears it like a cloak to cover what is really going on. And that isn't necessarily a bad thing.

Jorge Luis Borges' brilliant story "The Garden of Forking Paths" is about a spy doing spy things. But is it a spy story? Not exactly. Is George Orwell's Animal Farm a fable or a political satire that uses the fable form?

Okay. Getting to this week's favorite. A beautiful woman walks into the office of a private eye. Sound familiar?

Detective Andre has an office in downtown Rio. Marina wants him to find a man. Again, still familiar.

But now the ground shifts under us a bit. All she knows about the man is that he has been following her every day for weeks. Now he has stopped and she wants him to start again.

Andre and his sidekick, Fats - or is Fats the brains of the operation? - set out to find the guy. Much philosphizing occurs. Roland Barthes is invoked.

The place where what we might call experimental fiction - those cloaked-in-genre things - tend to fall apart is the ending. Some of these authors seem to take pride in not writing the last page, leaving you wondering what happened and why you bothered to read the damned thing.

Carniero is not guilty of that. I found his ending quite satisfactory, as was the whole story.

Sunday, December 18, 2016

Land of the Blind, by Craig Johnson,

"Land of the Blind," by Craig Johnson, in The Strand Magazine, October 2016 - January 2017.

It's Christmas Eve and Walt Longmire, sheriff of Absaroka County, Wyoming, is on his way to a hostage situation. A crazy druggie wearing only underpants has burst into a church and is pointing a gun at a woman's head, mumbling about God demanding a sacrifice.

And while Walt is the series hero the title clues you in that the star of this particular rodeo will be his deputy Double Tough, who lost one eye to a fire. I won't tell you what happens, but it's very satisfying.

It's Christmas Eve and Walt Longmire, sheriff of Absaroka County, Wyoming, is on his way to a hostage situation. A crazy druggie wearing only underpants has burst into a church and is pointing a gun at a woman's head, mumbling about God demanding a sacrifice.

And while Walt is the series hero the title clues you in that the star of this particular rodeo will be his deputy Double Tough, who lost one eye to a fire. I won't tell you what happens, but it's very satisfying.

Monday, December 12, 2016

Toned Cougars, by Tony Bellotto

"Toned Cougars," by Tony Bellotto, in Rio Noir, edited by Tony Bellotto, Akashic Books, 2016.

I have been known to complain about these Akashic Press books, specifically that the editors sometimes don't seem to know what noir is. No complaints about this story (which happens to be written by the book's editor). It follows the formula perfectly.

Our protagonist is a fortyish beach bum who makes his living romancing older women. His latest conquest, if that's the word, is older than his mother, but he finds himself falling in love, much to his discomfort.

Turns out she has a wealthy husband she doesn't much care for. Turns out she thinks our hero could solve that problem for her.

And if you have read any noir you may suspect it won't end with champagne and wedding cakes.

I have been known to complain about these Akashic Press books, specifically that the editors sometimes don't seem to know what noir is. No complaints about this story (which happens to be written by the book's editor). It follows the formula perfectly.

Our protagonist is a fortyish beach bum who makes his living romancing older women. His latest conquest, if that's the word, is older than his mother, but he finds himself falling in love, much to his discomfort.

Turns out she has a wealthy husband she doesn't much care for. Turns out she thinks our hero could solve that problem for her.

And if you have read any noir you may suspect it won't end with champagne and wedding cakes.

Monday, December 5, 2016

Played to Death, by Bill FItzhugh

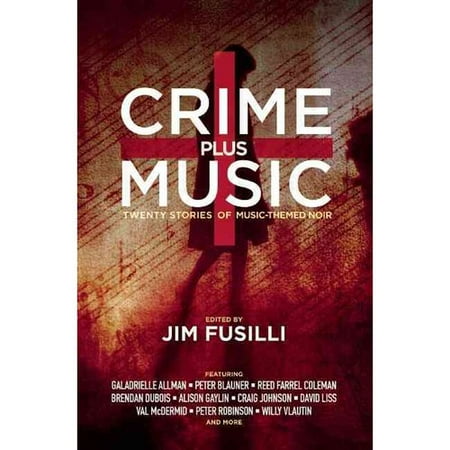

"Played to Death," by Bill FItzhugh, in Crime Plus Music, edited by Jim Fusilli, Three Rooms Press, 2016.

Decades ago I was privileged to hear a panel featuring Stanley Ellin, one of the great authors of mystery short stories. He declared that stories about murder should not be funny.

During the Q&A I reminded him of his story "The Day the Thaw Came to 127," in which (spoiler alert) the frustrated tenants of a New York apartment building burn their landlord for fuel.

"Well," he replied, "That was wish-fulfillment."

I bring that up because today's story falls into the same category, I think. Bill Fitzhugh worked in radio before turning to comic crime novels.

Grady, the main character of this story, is one of those guys who tells DJs what they are allowed to play. Specifically the fewest number of songs they can play over and over and over. He confronts somebody who is not fond of that format, but does speak Grady's language.

"You know how it works," the man said. "We had a good sample of the demographic we're trying to appeal to and we asked what they wanted, and this is what they said. We're just giving them what they asked for."

"Which is what?"

"Bad news for you, I'm afraid."

Did I mention the somebody has a gun?

I won't reveal what else happens. Tune back in after the news and sports.

Decades ago I was privileged to hear a panel featuring Stanley Ellin, one of the great authors of mystery short stories. He declared that stories about murder should not be funny.

During the Q&A I reminded him of his story "The Day the Thaw Came to 127," in which (spoiler alert) the frustrated tenants of a New York apartment building burn their landlord for fuel.

"Well," he replied, "That was wish-fulfillment."

I bring that up because today's story falls into the same category, I think. Bill Fitzhugh worked in radio before turning to comic crime novels.

Grady, the main character of this story, is one of those guys who tells DJs what they are allowed to play. Specifically the fewest number of songs they can play over and over and over. He confronts somebody who is not fond of that format, but does speak Grady's language.

"You know how it works," the man said. "We had a good sample of the demographic we're trying to appeal to and we asked what they wanted, and this is what they said. We're just giving them what they asked for."

"Which is what?"

"Bad news for you, I'm afraid."

Did I mention the somebody has a gun?

I won't reveal what else happens. Tune back in after the news and sports.

Sunday, November 27, 2016

1968 Pelham Blue SG Jr, by Mark Haskell Smith

“1968 Pelham Blue SG Jr.” by Mark Haskell Smith, in Crime Plus Music, edited by Jim Fusilli, Three Rooms Press, 2016.

I tried to resist this story. I really did. This led to a loud argument in my head.

-It's not a crime story.

-Of course it is.

-It's not a conventional crime story.

-So?

-But it's weird.

-So?

Quality won out.

Here's what makes it makes it weird: When was the last time you read a story written in first person plural?

You may say "A Rose for Emily," the masterpiece written by William Faulkner. But that story essentially has a standard third person omniscient narrator with just occasional uses of "We" to remind you that this is the community's viewpoint.

In Mark Haskell Smith's story, on the other hand, "We" is very much the main character. They are (It is?) an over-the-hill rock band, so meshed together that they speak as a unit. It's a shock when one of the members thinks about quitting and suddenly shifts from "one of us" to "he."

After a gig the band's equipment (including the titular guitar) is stolen but "we couldn't call the police because one of us was supposed to be home with an ankle monitor strapped to our leg."

So they go off in search of it. But single-minded they ain't. When the hunt takes them to a donut shop the rings of fat and sugar so mesmerize them they forget what they came for. "We are not detectives," they explain, primly.

No, but they are hilarious.

I tried to resist this story. I really did. This led to a loud argument in my head.

-It's not a crime story.

-Of course it is.

-It's not a conventional crime story.

-So?

-But it's weird.

-So?

Quality won out.

Here's what makes it makes it weird: When was the last time you read a story written in first person plural?

You may say "A Rose for Emily," the masterpiece written by William Faulkner. But that story essentially has a standard third person omniscient narrator with just occasional uses of "We" to remind you that this is the community's viewpoint.

In Mark Haskell Smith's story, on the other hand, "We" is very much the main character. They are (It is?) an over-the-hill rock band, so meshed together that they speak as a unit. It's a shock when one of the members thinks about quitting and suddenly shifts from "one of us" to "he."

After a gig the band's equipment (including the titular guitar) is stolen but "we couldn't call the police because one of us was supposed to be home with an ankle monitor strapped to our leg."

So they go off in search of it. But single-minded they ain't. When the hunt takes them to a donut shop the rings of fat and sugar so mesmerize them they forget what they came for. "We are not detectives," they explain, primly.

No, but they are hilarious.

Sunday, November 20, 2016

The Long Black Veil, by Val McDermid

"The Long Black Veil," by Val McDermid, in Crime Plus Music, edited by Jim Fusilli, Three Rooms Press, 2016.

Jess lives with relatives because, a decade ago when she was four years old, her mother murdered her father. That's the official story, but it turns out the truth is a lot more complicated. "There are worse things to be in small-town America than the daughter of a murderess," says her caretaker. "So I hold my tongue and settle for silence."

McDermid is a Scottish author but she writes well about "small-town America." This is a story about privileged rich kids clashing with folks from the poor side of town. Also about teenagers trying to figure out who they are and coming up with answers that may not please their neighbors.

I enjoyed this one a lot.

Jess lives with relatives because, a decade ago when she was four years old, her mother murdered her father. That's the official story, but it turns out the truth is a lot more complicated. "There are worse things to be in small-town America than the daughter of a murderess," says her caretaker. "So I hold my tongue and settle for silence."

McDermid is a Scottish author but she writes well about "small-town America." This is a story about privileged rich kids clashing with folks from the poor side of town. Also about teenagers trying to figure out who they are and coming up with answers that may not please their neighbors.

I enjoyed this one a lot.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)